Introduction

The term “Agentic AI” is now commonly used in industry conversations, yet its meaning often ranges from simple automation tools to advanced digital workers. Retail leaders typically envision Agentic AI as a capable junior employee able to understand goals, reason, take action across platforms, and learn, setting high expectations for implementation.

This broad perception is close to the research-based definition: systems that pursue goals, understand context, plan, act, and collaborate with other agents. In practice, however, many solutions labeled as agentic simply combine automation, machine learning, language models, and APIs.

In this discussion:

- Agentic AI means sophisticated, enterprise-level autonomous systems focused on defined objectives.

- Autonomous Workflow Orchestration (AWO) reflects current retail tools: smart workflows still guided by human priorities.

Key questions covered:

- What systems are in use today?

- Which technologies are mislabeled as agentic?

- What advancements are needed in tech, data, and processes to move from AWO to true agentic AI?

What People Think “Agentic AI” Is (And Why That Matters)

Many view an “agent” as more than a rule-based system. They expect it to handle complex tasks, strategize, and act independently. Technically, such agents should:

- Understand goals rather than just react to inputs.

- Make multi-step plans involving various systems.

- Select and sequence tools or APIs appropriately.

- Adapt when things go off course.

This distinction affects leadership expectations: if leaders think they’re getting fully capable agents, they may incorrectly assign responsibility. Confusing automation with autonomy can lead to inadequate oversight and accountability gaps. Accurate descriptions of “agentic AI” are crucial, as mislabeling advanced workflow automation may cause governance failures when organizations rely on abilities these systems don’t possess.

What AWO Really Is: Architectural Reality, Not Just Buzz

AWO is an integrated stack supporting autonomous workflows:

- The Workflow/RPA layer manages tasks between systems.

- Machine learning models assess risk, sort tickets, predict demand, and spot patterns.

- LLMs process unstructured text, summarize, draft, and converse.

- The integration fabric links retail and supply chain apps with APIs and queues.

- Rules and policies set boundaries, manage thresholds, and handle approvals.

Compared to traditional automation, AWO uses machine learning to trigger workflows based on data, rather than fixed rules. LLMs interpret complex inputs, enabling routing by predictions or classifications instead of basic logic. While adaptable, these systems don’t independently pursue high-level goals; they follow designed workflows.

In retail, AWO can validate return requests, resolve delivery issues, and spot shelf gaps from images. Problems occur when model assumptions fail, rules conflict, or policies change. Because workflows drive actions, solutions often require process redesign, underscoring the gap to fully goal-driven, agentic systems.

The Spectrum of Automation and Agentic Behaviour in Retail

The spectrum of automation and agentic behaviour provides leaders with a framework to benchmark their current capabilities and chart a path for future development. Retail organizations typically progress through four distinct stages, each with its own strengths, weaknesses, and operational implications.

The spectrum: Automation → AWO → Narrow Agents → Agentic Ecosystems

Stage 1: Rules Automation

At this stage, automation is driven by macros, scripts, and Robotic Process Automation (RPA) bots. The primary advantage of this approach is its predictability and controllability. However, these systems are inherently brittle; any change in user interface or data format can cause the automation to break, leading to disruption in operations.

Stage 2: Adaptive Workflow Orchestration (AWO)

AWO systems can adapt within established workflows but lack the ability to modify the workflow structure itself. These systems remain workflow-centric but incorporate machine learning (ML) and large language models (LLMs) to make smarter decisions within the flow. The strength of AWO lies in its ability to handle greater variation and reduce manual handoffs. The limitation, however, is that goals are externally defined and the workflow logic is still hard-coded, constraining the system’s ability to respond to new or unexpected challenges.

Stage 3: Narrow Agents

Narrow agents introduce the capacity to make decisions based on trade-offs, not just rigid rules. These domain-specific agents can reason within a tightly defined scope. For example, a pricing agent can select among pre-approved strategies within established guardrails, while a disruption-management agent may propose and sometimes execute remediation steps. At this stage, the distinction between a “smart workflow” and an “agent” begins to blur, as the system starts to optimize rather than merely execute scripted actions.

Stage 4: Agentic Ecosystems

In this most advanced stage, agents operate under high-level goals and possess autonomy in selecting methods. Multiple agents with different roles and perspectives collaborate, sharing goals or negotiating trade-offs such as margin, service level, and inventory risk. These agents are empowered to choose their tools and may even propose new process variants, reflecting a dynamic and adaptive approach to retail operations.

Current State and Key Takeaway

Most retailers today find themselves between Stages 2 and 3, with Adaptive Workflow Orchestration present in several workflows and a few narrow agent-like pilots underway. Despite these advancements, governance, data foundations, and integration patterns remain rooted in traditional workflow-centric models, rather than in structures that support agents capable of initiating or reshaping work.

Importantly, progression through these stages cannot be achieved in a single leap. Each stage introduces new potential failure modes, ranging from simple bot breakdowns to workflows making poor decisions, to agents optimizing for objectives that may not align with organizational goals. Leaders must be deliberate and explicit about which stage they are designing for, ensuring that systems and processes are properly aligned with their intended capabilities.

Practical Examples: Where Automation Excels and Where It Falls Short

Automated Refunds and Returns: The Limits of Autonomy

Automated refund and return processes demonstrate how advanced orchestration systems streamline routine workflows. The standard – or “happy path” – scenario is handled efficiently: the system classifies the return reason, checks applicable policies, processes the refund, and notifies the customer. However, the process becomes more complex when exceptions arise. Critical questions include: Who is responsible for resolving edge cases such as suspected fraud, chronic returners, or policy conflicts? Is the automated system empowered to weigh cost against customer goodwill, or does that authority remain with humans?

Typically, automation is permitted only within a defined risk band. For instance: if the risk score is below a certain threshold (X), the system approves the refund automatically; if the score falls between X and Y, the case is escalated; if above Y, the refund is blocked. This illustrates classic Adaptive Workflow Orchestration (AWO) – the system applies a business’s predetermined risk appetite on a larger scale but does not set or adjust that appetite itself.

Computer Vision in Planogram Checks: From Task Generation to Strategic Action

In another example, computer-vision-powered systems conduct planogram checks, detecting gaps on shelves and prompting the workflow to generate corrective tasks. The deeper, strategic questions are: Can the system reprioritize these tasks based on factors such as sales impact or labour constraints? Is it able to propose alternative merchandising layouts in response to local store behaviour?

At present, the answer is generally no. The system continues to follow a linear process: detect an issue, then raise a task. True agentic behaviour would involve the system analyzing a store’s unique traffic patterns and sales profile, proposing a new display layout, simulating the impact, and rolling out the change as a test.

The Analytical Gap in Current Automation

A common pattern emerges across these scenarios. The “sense” and “act” phases of automation are becoming more intelligent and hands-off. Yet, determining the broader objectives – deciding what trade-offs are acceptable and which “game” to play – remains mostly a human-driven and static process.

This highlights a key analytical gap. While much is said about “autonomous AI,” closer examination reveals that most autonomy is local and tactical, not global and strategic. As a result, Adaptive Workflow Orchestration delivers strong return on investment (ROI) but does not fundamentally transform the underlying operating model.

A More Rigorous Look at Future Agentic Scenarios

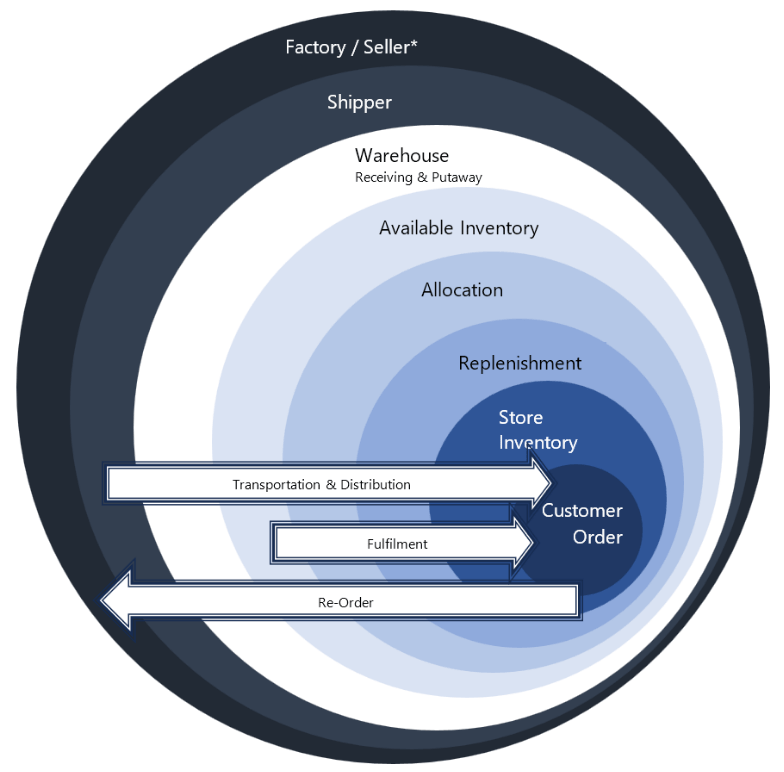

Let’s revisit the future supply chain scenario in a more structured way. When an agent spots a disruption, it goes through several processes: monitoring data continuously, maintaining contextual awareness of business-critical variables, and communicating efficiently with other agents to coordinate responses.

The replenishment agent, in turn, considers constraints like supplier lead times and contractual limits, understands service levels and margin goals, and prioritizes options that best fit business objectives.

As more agents are added, covering margins, stores, and customer interactions, the challenges shift from simply integrating systems to ensuring all agents share accurate information, resolve conflicts, and know when to involve humans.

These issues mean automation is not just about upgrading technology. Key concerns include who defines agent goals, how often they’re reviewed, and what oversight exists for agent decisions. As a result, agentic pilots tend to focus on narrow tasks, such as dynamic pricing or local optimization, rather than handling entire supply chains. The primary hurdles relate to governance, data quality, and accountability, not just technical sophistication.

The Leadership Imperative: Why the AWO vs. Agentic AI Distinction Matters

Mischaracterizing Automated Workflow Orchestration (AWO) as fully agentic artificial intelligence can lead to notable repercussions for leadership and organizational effectiveness. When this distinction is not explicitly acknowledged, three primary challenges frequently emerge: architecture drift, risk blind spots, and talent misalignment.

1. Architecture Drift

Integrating agents into a workflow-centric environment without comprehensive planning often results in their function being limited to advanced decision points rather than serving as fundamental system components. Such an approach neglects critical design considerations including shared memory, a unified goal repository, and event-driven architecture, each essential for enabling agents to operate as integral contributors within the broader ecosystem.

2. Risk Blind Spots

The presumption that “the agent knows what it’s doing” may result in inadequate investment in vital safety and governance controls. These include:

- Observability: Mechanisms enabling tracing and explanation of agent decisions.

- Kill Switches: Capabilities to quickly intervene and suspend agent actions when necessary.

- Sandboxes: Controlled environments for safely testing new agent behaviours prior to deployment.

3. Talent Mismatch

Prioritizing recruitment of only prompt engineers overlooks the comprehensive skills required for effective agentic AI implementation. Beyond technical expertise, organizations benefit from engaging:

- Professionals skilled in designing robust machine–human workflows.

- Individuals capable of defining agent objectives, constraints, and developing meaningful evaluation frameworks.

Retail-Specific Sequencing Challenges

Within the retail sector, misconstruing “buying agents” may result in omitting foundational activities such as:

- Data cleansing and standardization for products, locations, and customers.

- Streamlining process variants to minimize operational complexity.

- Establishing standardized integrations across Order Management Systems (OMS), Warehouse Management Systems (WMS), Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP), and e-commerce platforms.

Neglecting these prerequisites often causes agentic initiatives to stagnate or devolve into isolated, non-scalable solutions. This may foster the erroneous belief that agents are inadequate, when in fact, the organization was insufficiently prepared for adoption.

Importance of Distinguishing AWO from Agentic Ecosystems

Differentiating between AWO and agentic ecosystems is imperative, as it significantly influences leadership approaches and talent requirements. While workflow enhancements primarily necessitate expertise in workflow engineering and machine learning/large language models (ML/LLM), transitioning to agentic systems demands reimagining organizational decision-making structures and recruiting individuals adept at architecting resilient socio-technical systems.

Practical Steps for Leaders: Navigating Agentic AI in Retail

If you are a CIO, COO, or Head of Digital responding to board-level questions about “agentic AI,” the following structured approach outlines what you should focus on over the next 12 to 18 months.

1. Maximize the Value of Automated Workflow Orchestration (AWO)

- Identify five to ten high-volume, rules-based processes. Typical examples include returns management, handling order exceptions, vendor queries, and store-level tasks.

- Redesign these processes explicitly as AWO, ensuring each has defined inputs, outputs, and key performance indicators (KPIs). Carefully consider where machine learning or large language models (ML/LLMs) can add measurable value.

- Implement instrumentation for these flows to track and measure improvements such as reduced cycle times, lower error rates, and customer impact.

2. Develop Targeted Agent Pilot Projects

- Deliberately design one or two narrow agent pilot initiatives. Select domains with clear objectives and manageable risks, such as dynamic pricing within set ranges, markdown optimization, or tuning localized assortments.

- Allow agents to propose actions within predetermined guardrails. Initially, keep humans in the approval loop, gradually shifting to exception-only review as confidence in the system grows.

- Treat these pilots as experiments in operational autonomy, not just as new digital tools. Document and analyze any challenges encountered, including data quality issues, policy conflicts, or trust barriers.

3. Lay the Foundation for “Agent Readiness”

- Data: Clearly define what data agents will need to operate cross-functionally across the organization.

- Events: Transition from nightly data batches to real-time event streams for key operational signals.

- Governance: Establish an “autonomy matrix” to clarify which decisions can be fully automated, which require human review, and which should remain exclusively human-driven for the time being.

By systematically following these three steps, you will be building the necessary infrastructure and capabilities to progress from today’s orchestrated copilot models to tomorrow’s more autonomous agentic ecosystems, without exposing your organization to undue risk or succumbing to industry buzzwords.

Reframing “Progress” in Retail AI

The core message is not that “Agentic AI is years away, so wait,” but rather: “Retail is currently experiencing an AWO phase that offers notable value, and the approach taken to AWO will either position businesses for agentic ecosystems in the future or pose significant challenges later.”

If AWO implementations are opaque, rigid, and confined to singular applications, they limit long-term progress. Conversely, instrumented, integrated, and well-governed AWOs serve as foundational platforms for developing agent-based systems. While the underlying technologies may be similar, the resulting strategic trajectories differ substantially.

For organizational leaders, the critical consideration is not simply whether agents have been adopted, but whether today’s automation strategies are being designed to enable greater autonomy in the future, should that become desirable. Affirmative action in this regard ensures that organizations are leveraging current capabilities to strategically prepare for a transition toward autonomous retail operations.