As we continue to unlock the secrets of quantum gravity and teleportation, each discovery invites us to ponder just how much more there is to unveil, a testament to the infinite possibilities that lie hidden within the quantum tapestry of our universe. The next revelation may be just around the corner, waiting to astonish us all over again, bringing us closer to understanding our universe, and our place within it.

Introduction

Imagine voyaging across the galaxy at warp speed, like in Star Trek or Star Wars, where starships zip through cosmic shortcuts called wormholes. While these cinematic adventures may seem far-fetched, the wildest twist is that wormholes aren’t just a figment of Hollywood’s imagination—quantum physics hints they might truly exist, emerging from the very fabric of quantum entanglement. This remarkable idea flips our understanding of the universe: space and time could actually spring from invisible quantum connections, reshaping what we know about black holes and the universe itself.

This revolutionary perspective burst onto the scene in 2013, thanks to Juan Maldacena and Leonard Susskind, who suggested that whenever two systems are maximally entangled, a wormhole connects them, anchoring each system at opposite ends [1]. Building on the pioneering work of Einstein, Podolsky, and Rosen (EPR) on quantum entanglement and the Einstein-Rosen (ER) description of wormholes, Maldacena and Susskind daringly bridged quantum physics with general relativity, inviting us to think of our universe as far stranger, and far more interconnected, than we ever imagined [2].

Einstein-Rosen Bridges and the Origins of Wormholes

In their seminal paper, Einstein and Rosen encountered the concept of wormholes while seeking to describe space-time and the subatomic particles suspended within it. Their investigation centred on disruptions in the fabric of space-time, originally revealed by German physicist Karl Schwarzschild in 1916, just months after Einstein published his theory of relativity.

Schwarzschild demonstrated that mass can become so strongly self-attractive due to gravity that it concentrates infinitely, causing a sharp curvature in space-time. At these points, the variables in Einstein’s equations escalate to infinity, leading the equations themselves to break down. Such regions of concentrated mass, known as singularities, are found throughout the universe and are concealed within the centres of black holes. This hidden nature means that singularities cannot be directly described or observed, underscoring the necessity for quantum theory to be applied to gravity.

Einstein and Rosen utilized Schwarzschild’s mathematical framework to incorporate particles into general relativity. To resolve the mathematical challenges posed by singularities, they extracted these singular points from Schwarzschild’s equations and introduced new variables. These variables replaced singularities with an extra-dimensional tube, which connects to another region of space-time. They posited that these “bridges,” or wormholes, could represent particles themselves.

Interestingly, while attempting to unite particles and wormholes, Einstein and Rosen did not account for a peculiar particle phenomenon they had identified months earlier with Podolsky in the EPR paper: quantum entanglement. Quantum entanglement led quantum gravity researchers to fixate on entanglement as a way to explain the space-time hologram.

Space-Time as a Hologram

The concept of space-time holography emerged in the 1980s, when black hole theorist John Wheeler proposed that space-time, along with everything contained within it, could arise from fundamental information. Building on this idea, Dutch physicist Gerard ‘t Hooft and others speculated that the emergence of space-time might be similar to the way a hologram projects a three-dimensional image from a two-dimensional surface. This notion was further developed in 1994 by Leonard Susskind in his influential paper “The World as a Hologram,” wherein he argued that the curved space-time described by general relativity is mathematically equivalent to a quantum system defined on the boundary of that space.

A major breakthrough came a few years later when Juan Maldacena demonstrated that anti-de Sitter (AdS) space—a theoretical universe with negative energy and a hyperbolic geometry—acts as a true hologram. In this framework, objects become infinitesimally small as they move toward the boundary, and the properties of space-time and gravity inside the AdS universe precisely correspond with those of a quantum system known as conformal field theory (CFT) defined on its boundary. This discovery established a profound connection between the geometry of space-time and the information encoded in quantum systems, suggesting that the universe itself may operate as a vast holographic projection.

ER = EPR

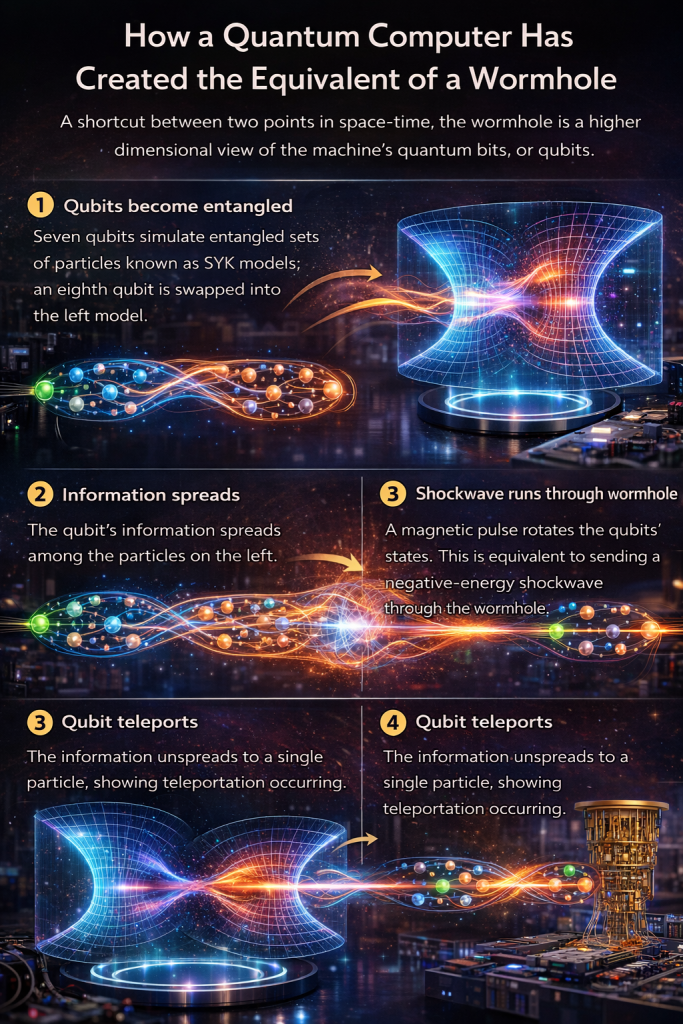

Recent advances in theoretical and experimental physics have leveraged the SYK (Sachdev-Ye-Kitaev) model to explore the practical realization of wormholes, particularly in relation to quantum entanglement and teleportation. Building on Maldacena’s 2013 insight that suggested a deep connection between quantum entanglement (EPR pairs) and wormhole bridges (ER bridges)—summarized by the equation ER = EPR—researchers have used the SYK model to make these ideas more tangible. The SYK model, which describes a system of randomly interacting particles, provides a mathematically tractable framework that mirrors the chaotic behaviour of black holes and the properties of quantum gravity.

In 2017, Daniel Jafferis, Ping Gao, and Aaron Wall extended the ER = EPR conjecture to the realm of traversable wormholes, using the SYK model to design scenarios where negative energy can keep a wormhole open long enough for information to pass through. They demonstrated that this gravitational picture of a traversable wormhole directly corresponds to the quantum teleportation protocol, in which quantum information is transferred between two entangled systems. The SYK model enabled researchers to simulate the complex dynamics of these wormholes, making the abstract concept of quantum gravity more accessible for experimental testing.

By 2019, Jafferis and Gao, in collaboration with others, successfully implemented wormhole teleportation using the SYK model as a blueprint for their experiments on Google’s Sycamore quantum processor. They encoded information in a qubit and observed its transfer from one quantum system to another, effectively simulating the passage of information through a traversable wormhole as predicted by the SYK-based framework. This experiment marked a significant step forward in the study of quantum gravity, as it provided the first laboratory evidence for the dynamics of traversable wormholes, all made possible by the powerful insights offered by the SYK model.

Conclusion

Much like the mind-bending scenarios depicted in Hollywood blockbusters such as Star Trek and Star Wars, where spaceships traverse wormholes and quantum teleportation moves characters across galaxies, the real universe now seems to be catching up with fiction.

The remarkable journey from abstract mathematical conjectures to tangible laboratory experiments has revealed a universe far stranger, and more interconnected, than we could have ever imagined. The idea that information can traverse cosmic distances through the fabric of space-time, guided by the ghostly threads of quantum entanglement and the mysterious passageways of wormholes, blurs the line between science fiction and reality.

As we continue to unlock the secrets of quantum gravity and teleportation, each discovery invites us to ponder just how much more there is to unveil, a testament to the infinite possibilities that lie hidden within the quantum tapestry of our universe. The next revelation may be just around the corner, waiting to astonish us all over again, bringing us closer to understanding our universe, and our place within it.