My work is about helping clients and organizations bring their ideas to life, transforming understanding into development, and development into reality, with as little friction and as much functionality as possible.

Lately, I have been reflecting on what drew me, as a designer, to write about topics such as artificial intelligence and quantum computing. I have been fascinated with both topics and how they have transformed that way we view the world. Everything we see today in terms of advancements in AI and quantum computing started with an idea, brought to life through innovation and perseverance.

In AI, there was the idea that machine learning would transform the way we do business by leveraging large amounts of data to provide valuable insights, something that would not be easily attainable through human effort. In quantum computing, there was the idea that applying the way particles behave in the universe to computing would unlock a vast potential for computing capabilities and power, beyond what classical computers can achieve. So many other advancements and achievements in AI and quantum computing continue to be realized through the conception of ideas and the relentless pursuit of ways and methods to implement them.

Everything starts with an idea

Beyond AI and quantum computing, everything we see around us started with an idea, brought to life through continued and persistent effort to make it a reality. Every building we see, every product, every service and all material and immaterial things in our lives are the product of an idea.

As a designer and product architect, I also help make ideas a reality through persistent effort and the application of methodology that lays a roadmap for the implementation of those ideas. Similarly, AI and quantum computing are fields that are bringing novel and exciting concepts to life through the development and application of scientific methodology.

While thinking about all of this, I pondered how I would define my work and role as a designer. How would I describe my work, knowing that most of us use technology without thinking about the journey a product takes from idea to experience? What value do I bring to organizations that hire me to help them with their problems? In an age where products are incorporating ever more advanced and sophisticated technology, as is the case with AI and quantum computing, how does my work extend beyond simply developing designs and prototypes?

To answer these questions, I am drawn back to the fact that everything around us starts with an idea. As a designer, it is extremely rewarding to me to help make ideas for my clients a reality while navigating the conceptual, technical and implementation challenges.

Making the invisible useful

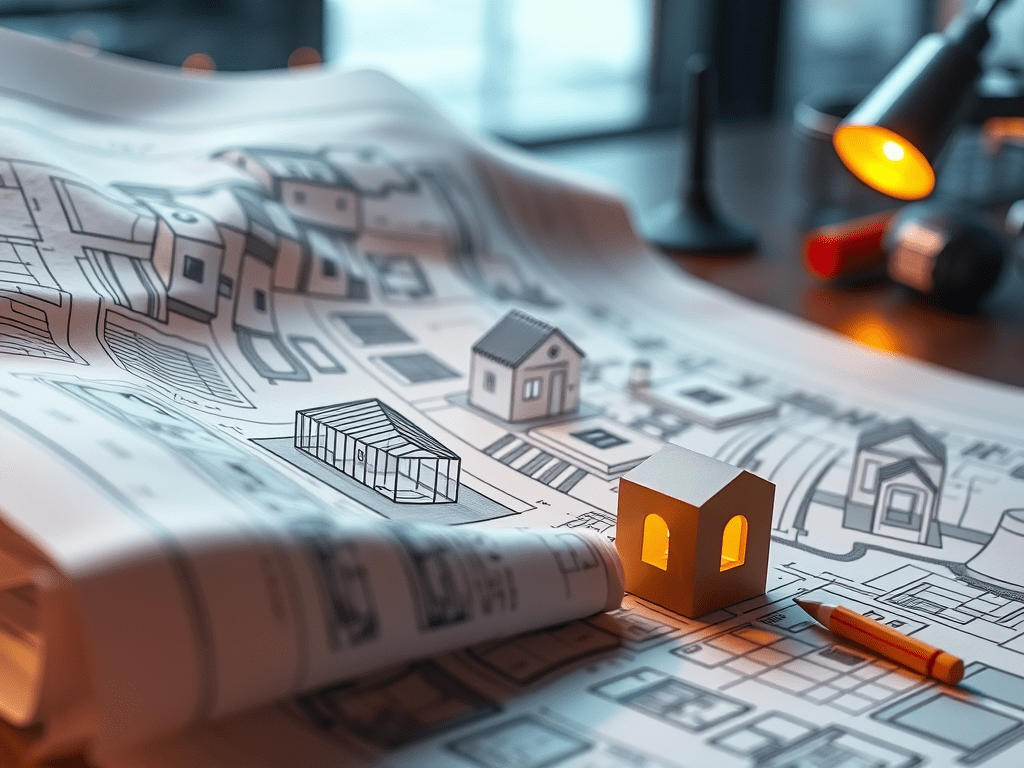

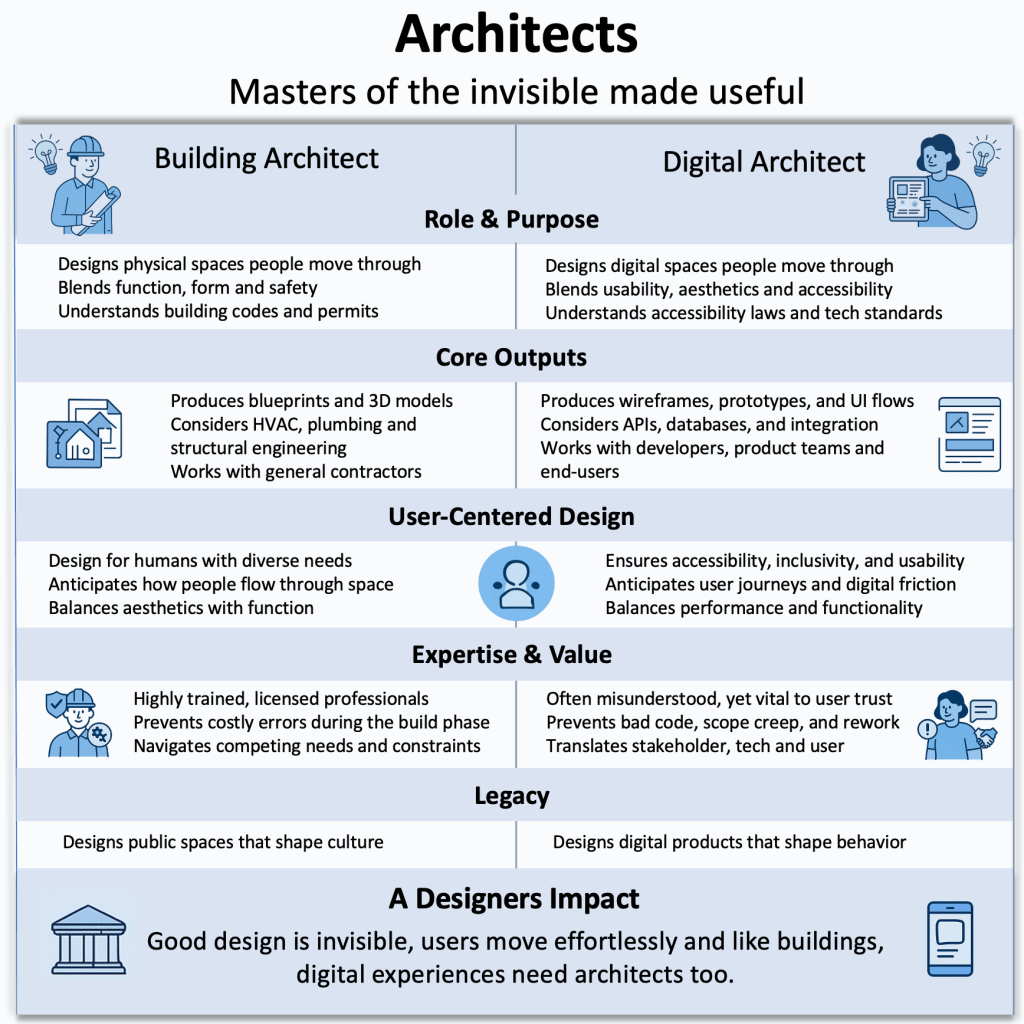

I’ve been thinking a lot about the similarities between how we design physical spaces and how we design digital ones. Just like a building starts as an idea in an architect’s mind, so are the products that I work on and help a multitude of organizations bring to life. As a designer, I help lay the foundations for a product idea by thoroughly understanding the motivations and needs behind it, and what benefits and improvements implementing it would bring.

Buildings serve needs by providing housing for people or serving as places to work, and for businesses and organizations to operate. A well-designed building offers an effortless flow that draws people in and makes them want to stay. Similarly, great digital design allows for seamless navigation, creating an experience that feels natural and engaging. Before an architect devises plans and drawings for a building, they must first maintain a clear vision of the idea in their mind, understand the needs behind it and ensure that their designs and plans meet those needs.

From there, the idea and concept of the building in the architect’s mind are translated into plans and drawings. Those plans are drawn and shared with a builder, who in turn collaborates with the architect to bring them to life. Without the architect and their clear vision of the idea and concept behind the building, the building would not exist, at least not in the shape and form that the architect would have imagined. It would not properly serve the needs and bring about the benefits that accompanied the original idea.

Just like a building architect, as a product architect I must also understand the needs behind digital products to create experiences that truly serve the user. Through this process, I envision flows and interactions that will enable users to achieve their goals in the simplest and easiest way possible, reducing friction while also achieving the desired business value and benefit. Like an architect, I collaborate with members of technical teams so that the idea behind the product can be realized to its full potential through detailed roadmaps, designs and prototypes.

An architect must possess technical and creative skills that enable them to visualize the idea of a building. The same is true for me as a product architect. Without the ability to clearly articulate complex technical concepts through detailed designs and specifications while also applying a creative lens, product ideas would not be realized to their full potential.

In summary, how do I define my work? My work is about helping clients and organizations bring their ideas to life, transforming understanding into development, and development into reality, with as little friction and as much functionality as possible. I can help you and your organization achieve the same. Let me show you how.