Introduction

In today’s rapidly evolving digital world, our interactions with technology are no longer limited to simple interfaces and straightforward feedback. The growth of cloud infrastructure, the explosion of big data, and the integration of advanced Artificial Intelligence (AI) have transformed the very foundation of how humans connect with systems. As applications become more intelligent, pervasive, and context-aware—operating seamlessly across devices in real-time—users expect more fluid, responsive, and personalized experiences than ever before. These expectations challenge the boundaries of traditional Human-Computer Interaction (HCI) and User Experience (UX) models, which were not designed for such complexity or dynamism.

Legacy frameworks like Human-Centred Design (HCD), User-Centred Design (UCD), the Double Diamond model, and Design Thinking have provided structure for decades, yet their sequential stages and lengthy feedback loops can’t keep pace with the demands of today’s interconnected, AI-driven world. To design experiences that truly resonate, we must rethink our approach—moving beyond rigid methodologies and embracing new paradigms that account for the unpredictable, adaptive nature of modern technology. The future of HCI calls for innovative, human-centred AI design strategies that acknowledge the unique capabilities and limitations of intelligent systems from the very start [1].

Quantum User Experience (QUX): An Alternative Perspective for HCI

When examining ways to enhance Human-Computer Interaction (HCI) methodologies, it becomes apparent that these approaches share similarities with the fundamental phenomena underlying nature and life itself. Drawing inspiration from Quantum Mechanics, we can establish a theoretical analogy to HCI, which gives rise to the concept of Quantum User Experience (QUX). QUX offers a distinct departure from traditional User Experience (UX) models in several ways [2]:

- Fluidity: QUX is not rigid, thus enabling experiences to be more dynamic and adaptable.

- Adaptability: QUX is not linear, allowing experiences to evolve in response to users’ changing needs.

- Mathematical Foundation: QUX is not random; it leverages mathematical data derived from measurements and research on user behaviour. This approach integrates feedback from previous processes and their associated data into new experiences.

- Temporal Definition: QUX is not infinite; experiences are distinctly defined in time, avoiding endless cycles of testing and iteration.

To reinforce this theoretical framework, the digital cosmos is conceptualized as the global network—such as the internet—functioning on two key scales: the macroscopic scale, which encompasses phenomena that are detectable, analyzable, and able to be influenced at a broad level across the network; and the microscopic scale, which refers to aspects that are perceived and felt, yet not directly observed or measured.

In the digital cosmos, three core entities serve as the foundation for its structure: Agents, Interactions, and Objects. Agents encompass not only users, but also any entity capable of engaging with others, such as bots, engines, or platforms. Interactions refer to the exchanges or communications that occur between these agents, facilitating connections and the flow of information. Objects represent the wide range of content found within the global network, including text, audio, and visual elements, all of which contribute to the richness and diversity of the digital environment.

Within the Quantum User Experience (QUX) framework, experiences are categorized as either macro- or micro-experiences: macro-experiences encompass collective behavioural patterns that involve multiple entities and significantly influence individuals or groups, while micro-experiences represent individual responses to notable stimuli or events that hold personal significance and shape one’s overall perception or feelings. Together, these experiences form the cumulative fabric of QUX, contributing to the flow of information across the vast structure of the digital cosmos.

Quantum-Scale Behaviour of Agents, Interactions, and Objects in QUX

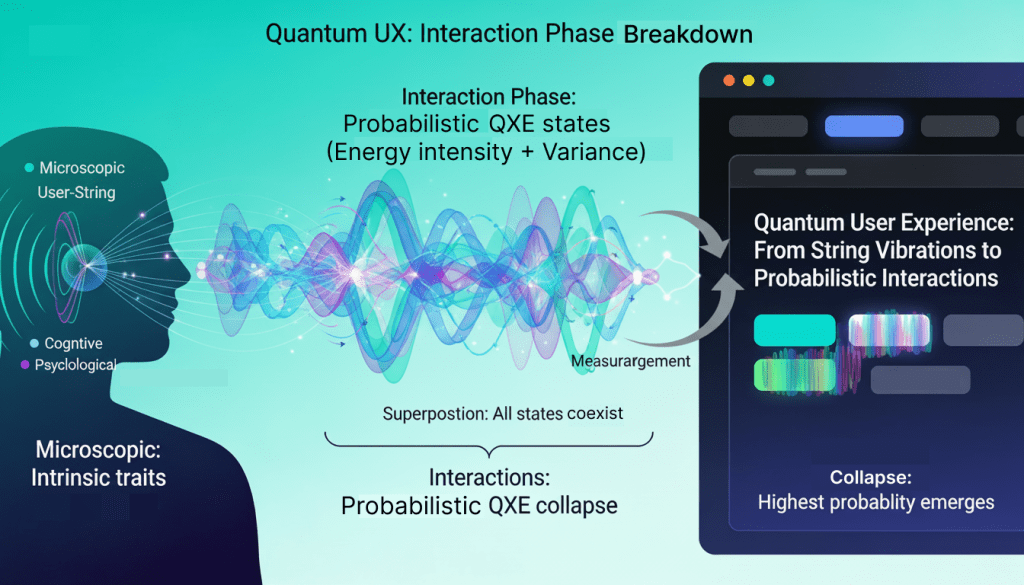

Within the QUX framework, the behaviours of Agents, Interactions, and Objects can be interpreted through a quantum lens, revealing how microscopic traits and probabilistic states shape the digital cosmos.

Agents are entities that exhibit microscopic characteristics—such as cognitive, social, or psychological attributes—which manifest as observable macroscopic behaviours. In the QUX perspective, Agents are conceptualized as “strings,” drawing a parallel to String Theory. This analogy suggests that all observable phenomena within the digital cosmos, at a macroscopic level, originate from the various vibrational states of these strings.

Interactions encompass the diverse behaviours that occur between agents (as vibrating strings) and objects, influenced by users’ perceptions and experiences over time. These interactions function as probabilistic quantum systems in superposition, described by their intensity (the strength of the interaction) and frequency (the variance of the interaction over time). Upon measurement, these probabilistic states collapse into observable Quantum Experience (QXE) states, allowing for a flexible and probabilistic approach to modelling user engagement.

Objects are defined as probabilistic Experience Elements (XL), which serve as the fundamental building blocks—such as buttons—of a system, application, or service. These objects possess a spectrum of possible values governed by probabilities and are characterized by discrete Experience Quanta (XQ) energy units resulting from user interactions. This framework supports real-time adaptability and multivariate evaluation of experiences, surpassing the limitations of traditional, rigid A/B testing methods.

Conclusion: Quantum Mechanics as Inspiration for QUX

The QUX framework draws profound inspiration from quantum mechanics, reshaping our understanding of human-computer interaction by adopting concepts like superposition, probabilistic states, and collapse. By viewing agents as vibrating strings—much like those in String Theory—QUX reimagines the digital cosmos as a domain where microscopic traits and behaviours coalesce into observable, macroscopic phenomena. Interactions function as quantum systems, existing in probabilistic superpositions until measured, at which point they collapse into tangible Quantum Experience (QXE) states. Objects, conceptualized as probabilistic Experience Elements, embody the quantum notion of possible values and energy units that adapt in real-time to user input. This quantum-inspired perspective enables flexible modelling of engagement, surpassing the limitations of classical, deterministic approaches.

As cloud computing, artificial intelligence, and quantum technologies advance, QUX motivates a paradigm shift in human-centred design and methodology. It champions adaptability, multivariate evaluation, and responsiveness to evolving user needs—mirroring the uncertainty and dynamism at the heart of quantum mechanics. In this way, QUX not only offers a novel theoretical foundation, but also empowers designers to meet the demands of a rapidly evolving technological landscape, ensuring that applications and systems remain attuned to the nuanced and changing nature of user experience.