The universe is not a closed book, but rather a narrative in progress—its future pages unwritten, its history ever-expanding. The digits that define time, instead of being predetermined, seem to emerge in concert with our unfolding experience, hinting at a reality that is both participatory and creative.

Introduction

Time: we all experience its steady march, feel its passing in our bodies, and witness its effects as trees stretch skyward, animals age, and objects wear down. Our everyday understanding of time is one of motion—a ceaseless flow from past, to present, into an open future. Yet, what if the very nature of time is not what it seems? Physics offers a perspective that is at odds with our intuition, challenging us to rethink everything we believe about reality.

Albert Einstein’s revolutionary theory of relativity upended this familiar notion, proposing that time is not merely a backdrop to events, but a fourth dimension intricately woven into the fabric of the universe. In his “block universe” concept, the past, present, and future exist together in a four-dimensional space-time continuum, and every moment—from the birth of the cosmos to its distant future—is already etched into reality. In this cosmic tapestry, the initial conditions of the universe determine all that follows, leaving little room for the unfolding uncertainty we sense in our lives [1].

Contrasting Views: Einstein, Quantum Mechanics, and the Nature of Time

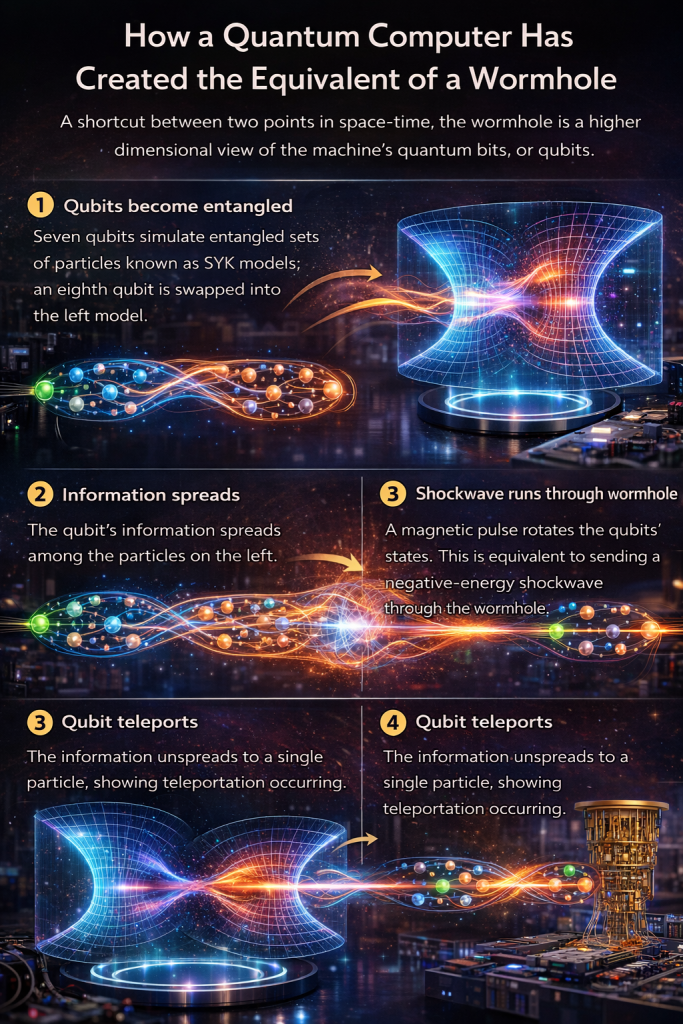

Most physicists today accept Einstein’s pre-determined view of reality, in which all events—past, present, and future—are fixed within the space-time continuum. However, some physicists who explore the concept of time more deeply find themselves troubled by the implications of this theory, particularly when the quantum mechanical perspective is considered. At the quantum scale, particles act in a probabilistic manner, existing in multiple states at once until measured; it is only through measurement that a particle assumes a single, definite state.

While each measurement of a particle is random and unpredictable, the overall results tend to conform to predictable statistical patterns. The behaviour of quantum particles is described by the evolution of their wave function over time. Quantum wave functions require a fixed spacetime, whereas relativity treats spacetime as dynamic and observer-dependent. This fundamental difference complicates efforts to develop a theory of quantum gravity capable of quantizing spacetime—a major challenge in modern physics [2].

Relativity, in contrast, insists that time and space be treated equally, making it necessary to introduce time as an operator and place it on the same level as position coordinates. In quantum mechanics, each particle is part of a system with many particles, and time and space coordinates are not treated equally. In such systems, there are as many position variables as there are particles, but only a single time variable, which represents a flaw in the theory. To overcome this, scientists have developed the many-time formalism, where a system of N particles is described by N distinct time and space variables, ensuring equal treatment of space and time [3].

If physicists are to solve the mystery of time, they must weigh not only Einstein’s space-time continuum, but the fact that the universe if fundamentally quantum, governed by probability and uncertainty. Quantum theory treats time in a very different way than Einstein’s theory. Time in quantum mechanics is rigid, not intertwined with the dimensions of space as it is in relativity.

Gisin’s Intuitionist Approach and Indeterminacy

Swiss physicist Nicolas Gisin has published papers aiming to clarify the uncertainty surrounding time in physics. Gisin argues that time—both generally and as we experience it in the present—can be expressed in intuitionist mathematics, a century-old framework that rejects numbers with infinitely many digits.

Using intuitionist mathematics to describe the evolution of physical systems reveals that time progresses only in one direction, resulting in the creation of new information. This stands in stark contrast to the deterministic approach implied by Einstein’s equations and the unpredictability inherent in quantum mechanics. If numbers are finite and limited in precision, then nature itself is imprecise and inherently unpredictable.

Gisin’s approach can be likened to weather forecasting: precise predictions are impossible because the initial conditions of every atom on Earth cannot be known with infinite accuracy. In intuitionist mathematics, the digits specifying the weather’s state and future evolution are revealed in real time as the future unfolds. Thus, reality is indeterministic and the future remains open, with time not simply unfolding as a sequence of predetermined events. Instead, the digits that define time are continuously created as time passes—a process of creative unfolding.

Gisin’s ideas attempt to establish a common indeterministic language for both classical and quantum physics. Quantum mechanics establishes that information can be shuffled or moved around, but never destroyed. However, if digits defining the state of the universe grow with time as Gisin proposes, then new information is also being created. Thus, according to Gisin information is not preserved in the universe since new information is being created by the mere process of measurement.

The Evolving Nature of Time

As we survey the landscape of contemporary physics, it becomes apparent that our classical conception of time is far from settled. Instead, it stands at the crossroads of discovery—a concept perpetually reshaped by new theories and deeper reflection. Einstein’s vision of a pre-determined reality, where all moments are frozen within the space-time continuum, offers comfort in its order and predictability. Yet, this view is challenged by the quantum world, where uncertainty reigns, and events transpire in a haze of probability until measurement brings them into sharp relief.

The friction between the determinism of relativity and the indeterminacy of quantum mechanics compels us to look beyond conventional frameworks. Quantum mechanics treats time as an inflexible backdrop, severed from the intricacies of space, whereas relativity insists on weaving time and space together, equal and dynamic. Gisin’s intuitionist approach further invites us to reflect on the very bedrock of reality—questioning whether information is static or endlessly generated as the universe unfolds.

This ongoing dialogue between classical physics and emerging quantum perspectives not only exposes the limitations of our current understanding but also sparks a profound sense of curiosity. If, as Gisin suggests, information is continuously created, then the universe is not a closed book, but rather a narrative in progress—its future pages unwritten, its history ever-expanding. The digits that define time, instead of being predetermined, seem to emerge in concert with our unfolding experience, hinting at a reality that is both participatory and creative.